Falling in Love with Alice: Fiction by Alon Preiss

A LONG, INTRICATE SERIES OF CONNECTIONS AND COINCIDENCES led Ewell to Alice, but once he met her, he was hooked, and he was hooked for good. He was thirty the summer that he first heard her voice over a crackling, long-distance telephone line, and she was a few years younger, but she was more successful than he was. She was, in fact, just weeks away from calling herself a millionaire, and she’d done it without much effort or special talent, just spinning up into the heavens with the rest of the American economy in the 1980s. It made Ewell long to be an American; so did Alice’s beautiful voice on the telephone. To walk in those bustling streets, to speak English in that crazy-charming accent with all its rough edges, to stand in the California smog drinking watery beer, to be a millionaire.

A MONTH LATER, SHE SENT HIM HER PHOTOGRAPH. Alice looked slight and delicate, with a smile that confounded and confused and charmed, and she was pretty enough to be called pretty in the real world. In the picture, she was leaning against a fence, and behind her were fields of corn. She had jet-black hair and smooth white skin, and pretty round cheekbones, and she looked like the physical embodiment of the type of girl who in sad novels would fall madly in love then die young. But her eyes hinted at steely resolve. Come visit me, Ewell! she wrote on the back of the photograph. He sent back his own picture. He was tall and lanky, and he didn’t look thirty — he was still outgrowing the awkwardness of youth. But she wrote to him that she loved his smile, and that he looked exactly as she had imagined from their phone calls and letters. What was that thing behind you in the picture? she wrote. Was that a fjord? Is that what that was? Write back soon!!! He wrote back: No. That was not a fjord.

THEIR NEXT BATCH OF LETTERS brought a downturn in the relationship. He wrote to her that he did not want to travel to America because he was afraid that she would not like him once he arrived there, and then he would be stuck alone in a country whose every billboard, every street corner, every crested butte, would remind him of Alice. She wrote to him that she was in love with a man named Mark, and she was filled with confusion. I loved him in college, and I broke up with him a few months after graduation. I thought it was a real breakup, but I realized later that I had done it to pressure him to marry me, or at least to become engaged to me. He took it as the end. He went onwith his life. And so did I. But I’m not really over him. And I thought you should know this. I don’t know why. All my love, Alice. They had begun very quickly to sign their letters with some variation of the word love, but neither had so far dared to place the word all by itself on the page. Ewell wrote back that she was right to be honest with him, and there are things in one’s life that one never gets over, and that’s just one of the dangers of being human, and he certainly would not hold such a thing against her. I once thought that I loved a woman named Aila, he wrote. And then, when it is no more, those feelings fade. If Fate means for you to be together, and to be in love, you will be. If not, you will not, and what must be false love will fade away, and one day you will be happy, and this is just part of the Adventure of Life. I am glad that you told me, and that I told you, because now we know each other better, and now we are closer. All my love, Ewell. She responded with something approaching glee. She’d had a very good day at work, had made a lot of money that day, then returned home to find his tender and beautiful letter waiting for her. This is how it made me feel! she wrote, and she enclosed a picture of herself smiling a very big smile. She also suggested that, if America made him so nervous, they might meet on “neutral territory,” someplace in Italy or Greece or someplace like that, in a remote and beautiful fishing village where they could swim and drink the sort of coffee that people drink in Europe and lie on the beach, and talk all day and get drunk and tan. He agreed in his next letter, and he suggested a place that he had read about that matched her description. The first night, they should stay at inns at the opposite end of town, spend their entire first day by themselves, getting used to the tranquil life and, in Alice’s case, recovering from jet-lag. Then, the second night, they would meet at a little restaurant in the center of town that looked out across the river at the castle, with the peacocks strolling around the grounds among the rose bushes. We will share a bottle of the local wine, and the scene will be perfect — the castle lit up in purple and blue and red, the waves of the ocean crashing on the shore, swans floating by on the river. If we do not like each other then, with everything so perfect, we will not like each other at all. That way, he explained, I could get on the next train, and I will be out of your life. You can still enjoy your vacation and have a very nice time. You will not be surrounded by my countrymen all looking and talking like me and driving you mad. I know that you work very hard, and if I do not please you in some way, I would not want that to ruin your rare vacation. With love, Ewell. P.S. Do not worry — if you decide to send me away, before I get on the train, I will help you plan your itinerary.

She actually telephoned him. “You don’t need to be so careful. I’m sure I will like you,” she insisted again. “I love your smile.”

“I love your smile too,” he said. “But just in case.”

A few weeks later, Ewell was riding in a train heading south for his first date with Alice, when an airplane passed overhead, angled at a slight incline in preparation for landing. Ewell wondered whether Alice were on that plane, and whether she were looking down at that exact moment, wondering whether Ewell were on the train. He told himself that he would remember to ask her that sometime during the week, but he never did. And every once in a while, for the rest of his life, he would wonder whether Alice had looked down at the train from her seat up in the clouds, and whether she had thought about him.

THE INN HE CHOSE was in the old section of town just a few feet away from an outdoor market. The inn had a steep winding staircase, and his room smelled like old wood. This was a good smell, Ewell decided; a smell Alice would like.

His first night in town, he bought a bottle of wine and sat out by the ocean, his feet buried in the sand, thinking about coming here the next night with Alice, practicing things he would say. Making sure that he didn’t tell her that thing about his past, that weird thing that scared girls away. And practicing his laugh. He had a “goofy” laugh, as another American girl had once described it. He would need to work on it. And so he did, laughing into the empty air, his laughter drifting out to sea on the chilly wind.

EWELL ARRIVED AT THAT CAFÉ EARLY, and everything was as he had described it to Alice. He asked for a table outside and sat in the cool breeze, looked around for Alice, then tried not to look around so much. He had brought a novel to read, but it was filled with brooding, and it did not hold his interest. Suddenly around the corner and out of the darkness came Alice, looking like her photograph but not like her photograph — now, relaxed, moving quickly through the night, her smile easier, her eyes wider and more hopeful; and then when she saw him stand up to greet her, she started to run, and when she’d reached his table, she was a little bit out of breath, and he smiled, and she leaned over and kissed him on the cheek, and she said, with a little laugh, “I’m Alice.”

ONE OF THE PEACOCKS on the opposite bank of the river was walking about with its tail open, which was a rare sight, but was not surprising, actually, given the magic of the evening as Ewell perceived it. After the first glass of wine, gazing admiringly across the river at the peacock bathed in purple light as it stood proudly before the centuries-old castle like a magician’s guard dog, Alice asked Ewell whether this was where he took all the American girls, and he said, “No. Only you,” and right after he said it he realized that she’d been trying to make some sort of a joke, and so he laughed, his big silly laugh, and it even felt silly as it came out of his throat, but it made her laugh twice as hard. On the second glass of wine, she was holding his hand, and she told him that his touch felt familiar, but not like anyone she’d ever known before tonight. “I don’t want to go back to my inn,” she said. They walked east through the town arm-in-arm along deserted, cobble-stone streets, stopping to kiss every few minutes in the electric-blue night. Back at the room, they threw themselves together with a hungry intensity, collided like shooting stars, and then they fell asleep wrapped in a tight embrace. When Ewell woke, Alice opened one eye. “See,” she said, “I told you I’d like you.”

AN HOUR LATER, after showering, Ewell came out of the bathroom naked, and Alice was sitting on the bed, squinting through her camera. She hesitated just a moment, focusing, and her ambush was ruined; Ewell protested, covered himself quickly with both hands, his white face a rosy blush. Alice put her camera down and pleaded with him. “Let me take a picture of your little man,” she said. “I won’t even get your face in the picture. Just your fellow.” He dropped his hands, looked down at Alice quizzically, ready to cover himself again if she raised the camera. Alice, admiringly, without any elaboration: “It’s like none other that I’ve ever seen or heard about.” Alice sitting naked and cross-legged on sticky and sweaty sheets, staring at her lover’s penis but going to great lengths to avoid saying the word, a word too embarrassing for her to utter. “A munchkin like none other,” Alice repeated. Ewell asked whether that was a good or a bad thing, and Alice replied, “An interesting thing, and a memorable thing,” and so he put his hands behind his head. Alice lowered her camera to crotch level, focused, and clicked the shutter.

THE VILLAGE WAS IN A CREVICE in the coast of the continent, well-known to European tourists but less frequented by Americans. Alice took pictures of everything, of bridges and trees, old buildings, used her zoom lens to take secret pictures of the fishermen, snapped many photos of Ewell smiling his uneasy smile. Ewell had lost his camera on the train, but Alice promised him that she would send him copies from America. They drank coffee and wine every day and grew dark in the sun. Did Alice tell jokes? Had she led an interesting life? They talked almost non-stop, but Ewell soon enough would wish that he had written down some of the things that Alice had said, because he would remember only assorted impressions of their days together, sometimes only colors. Alice sitting in the glistening white European sands in front of the dark ocean, wearing only a blue bikini bottom and stretching her thin legs out in front of her, toe-nails painted pink and purple, the summer heat beating down on her. She turned over on her side, walked her fingers up his arm and brushed them across his shoulder, then touched his face with the palm of her hand, and her smile was brighter than even the sun, and this moment burned a memory in his mind, so that, in the years to come, whenever he thought of Alice, this was the image that would appear to him, polished and perfected by the passage of time.

ON THEIR FOURTH NIGHT, Alice and Ewell sat in the cool night, their arms wrapped about each other in the darkness, looking out from their terrace at the narrow side street three floors below, lit up by the glimmer of the stars and the glow of the moon. A thin young man walked along in the moonlight, for some reason carrying a rather large sheep. He seemed to be having some trouble with the sheep; it kept squirming in his arms, and the man looked tired. He glanced up at Alice and Ewell, shouted something in his language; then he laughed. “What did he say?” Alice asked, and Ewell said he wasn’t sure. Alice sort of laughed, and Ewell reddened. Suddenly, he wanted Alice to know something about himself, his one and only rather remarkable skill. When he was a little boy, he had learned to read Chinese, literally in weeks, then had turned his attention to Japanese, then Korean, then some of the more obscure languages of Asia. He could never learn to speak or hear any foreign language at all with any sort of grace, not even the easy ones, like English and French. But those little pictures flowed through his head as though they were old friends. Back then, doctors claimed that, in this one area, he was some sort of genius, and he wanted Alice to know about this. He wanted her to know that she was spending the week with someone who, at least in one way, was remarkable, as remarkable as she was. He didn’t know exactly how to broach this subject.

Alice leaned back against Ewell, the softness of her hair against his face.

“Do we know each other yet?” he asked. “There are two Alices so far — the one whose handwriting I know so well, and the one whose voice I hear in the dark.”

“We know each other,” she said. “The important things. Like looking into your eyes and seeing your soul and knowing what’s in there.” She turned and smiled at him and laughed. “Stuff like that,” she added, self-mockingly. Then, quietly and more seriously: “Stuff like how when I first saw you at your table, and I suddenly recognized you in the night, I wanted to know you forever.”

Ewell let this comment float through his body, warm and soothing like a glass of red wine. Then he said, “And I felt that way too; even from before, from before you came into the light, before I even saw you, when I just felt that you were about to come in from the street. Something that I felt, I don’t know why or how.” He blushed furiously, but he thought that probably Alice couldn’t tell in the dark.

“Really?” Alice exclaimed, touched at this incoherent, extrasensory confession. “Is that really true?”

Ewell nodded.

“Well,” Alice said. “That’s so sweet.”

“But do you want to know me better?” he asked. “To know me factually.” This word sounded funny to him when he said it, and he wondered whether it sounded right to Alice, and whether his bad spoken English was half his charm.

“Sure,” she said. “Sure I would.”

“Ask me something about myself, then.”

“Hmm,” Alice said, scrunching up her face in a caricature of concentration. “Okay, I got it. What’s your favorite movie?” she asked.

“That’s not important.”

“It is,” she said. “The unimportant things are the most important, if you want to get to know a person. For example, my favorite song — my absolute favorite song in the world — is Frank Mills. That could probably tell you all kinds of things about me, if you wanted to give it serious thought. So tell me your favorite movie, okay?”

“All right.” Ewell thought for just a moment, then he said something that Alice couldn’t understand, and he explained that it was a movie made in his country when he was a little boy and that he didn’t expect her to know it. She asked him what it was about, but he said that he couldn’t explain it in English — it was about something unique to his country, an emotion that Americans couldn’t understand, and there was no word for it in English.

“Okay, then,” Alice said, “what’s your second favorite movie?” “Casablanca,” Ewell said.

Alice wanted to know why.

“It’s romantic — she thought her husband was dead, then she walks into his café all of a sudden. The two of them getting to know each other again, in a foreign place. In a place like this. A little town all full of — what’s the word?”

“Ewell!” Alice laughed. “Humphrey Bogart wasn’t the husband that Ingrid Bergman thought was dead! That was the other guy! The jerk she doesn’t really love who ruins everything! She found Humphrey Bogart, the man she really loved, only because she thought her husband was dead, then she had to leave Bogart when she discovered that her husband was still alive, then she had to leave him again to fight Nazis!”

“Oh yeah,” Ewell said, and he laughed. “Well, in my country people don’t really think about their favorite movie the way Americans do.” He didn’t mention to her that he’d said that Casablanca was his second favorite movie only because she was an American and he’d figured that she probably loved Casablanca. As a matter of fact, Ewell came from a family of die-hard and unrepentant Nazi sympathizers, and Casablanca had always made them all rather uncomfortable, come to think of it, though he did not admit this to Alice, nor did he admit that his second favorite movie was really the 1943 German version of Baron Müenchhausen. Now he most desperately yearned to tell Alice about his little area of linguistic brilliance, but Ewell could think of no way to work it into the conversation that would not sound haughty and self-inflating. So he never mentioned it.

SOME HOURS LATER, lying in bed, the blinds closed and the room completely dark, Alice was still buzzed on wine and romance. “I wish we could stay in this village forever,” she said; and also, “Don’t just leave me and go away, Ewell.” Alice said she wished she and Ewell could freeze this moment and just live in it until the universe collapsed in on itself. Ewell agreed with a wholehearted smile that she could not see in the dark, then with a sympathetic and loving laugh, though the idea of the universe collapsing in on itself — rather than expanding onward and outward while humanity generated new forms of energy to ensure survival of the species, which he’d thought was the currently accepted scientific view of the future of mankind — caused him to brood for a moment.

THE NIGHT OUTSIDE still pitch dark. “Tell me your goal, Ewell,” Alice said, sounding half-asleep, and he said that he intended, someday, to cure a terrible disease. “Have you decided which terrible disease?” she asked, and he said that he had, that it was a very rare illness, that it afflicted only a hundred people each year, and that he was sure that she had never heard of it. Quickly, he turned the conversation to Alice. “Tell me your perfect life,” Ewell said, and Alice began imagining. “I have made all my money,” she said, “and I am independent, and I don’t need to rely on anyone. I have a child — first a baby, then she grows to a little girl, then a big girl. Only one. Absolutely, I only have one in this life. She looks up to me and wants to be just like me, and I teach her all about life. We travel all over the world together, and she’s a spoiled girl, but also a very smart girl, and a very nice girl.” After a pause: “I think that’s it.”

“And a man?” Ewell asked. “In this perfect life, is there a man?”

Alice laughed, and then she added, smoothly, “Of course. I forgot to mention it, Ewell, dear. There’s a man, too. A funny European man.”

ON THE MORNING of their fifth day together, the telephone woke them at five. Ewell answered it, then he passed the receiver to Alice, and he muttered a woman’s name to her. “My assistant,” Alice groaned. Rubbing her eyes, she stuck the telephone handset on the pillow under her ear. She listened for a while. She groaned again, this time even more painfully. Ewell began to worry. She whispered unfamiliar phrases. What about X? and have you tried Y? and whatever happened to Z? Each question elicited an unheard response that apparently made Alice feel even worse. “Look,” she finally said, “is this something that I can solve right now?” and after another pause, she said, “That’s right — it was a rhetorical question. There’s nothing I can do to help over the phone. And my hopping on a plane and flying back today will only bust the bank even more, right?” Another long pause. “Yes,” she sighed, “you were right to call me, just to let me know. But now leave me alone, okay? Let me enjoy my last days as a rich woman, okay?” She nodded slowly, with deep resignation. “It’s not your fault,” she said. “If we go bust when I get back, we go bust when I get back.” She said a few more things that didn’t make sense to Ewell in context, and then she hung up the telephone, and she lay back in bed, her body tense. He looked over at her, and she no longer seemed to be here with him in this room; the telephone had stolen Alice, and now she was gone. He put a hand on her bare shoulder, and she shook him away.

“Just tell me what’s the matter,” he said to her, as the two of them sat side by side, in the middle of the woods in a small clearing beside a stream. Birds he had never before seen flew from branch to branch, and little furry animals scurried about, hoping he or Alice would throw them a scrap of food. The stream flowed by, over large rocks jutting out of the water, around the bend and off into the far distance, almost noiselessly. They were eating sandwiches that they had bought in a local shop.

“I don’t want to talk about real life,” Alice insisted. “Just let me relax, okay?”

They settled into an awkward silence. He reached over and touched her hand. She stiffened.

“I’m sorry,” Alice said, and she really did sound sorry. “Please. ”

He moved his hand away.

WALKING ON THE NARROW PATH back to town, Alice was rigid and unsmiling, thinking about her mysterious catastrophe.

“Are you relaxing yet?” Ewell said.

He’d intended this as a joke, but she did not seem to understand. “Ewell,” Alice said. “I’m trying, okay? Please don’t pressure me to relax.” She was at once plaintive and challenging.

“I didn’t mean to pressure you,” Ewell said softly.

He stood three feet away from her; the distance between them felt like a concrete wall.

“Don’t you know that you can’t pressure someone to relax?” Alice said again.

“I was just trying to make you laugh,” Ewell said.

Alice sighed. “It’s not working,” she said. “Just be quiet, okay?”

Ewell left her alone for a few minutes, but then, at a particularly beautiful bend in the path, he looked again at the anger and pain on her face, and he broke his silence.

“I care very much about you, Alice. Your problems are my problems.”

“No, Ewell,” she said. “They are not your problems. I will return to America to face destitution. You will return to your welfare state.”

“I don’t understand what you’re saying,” he replied. “Are we debating European socialism?”

“Are you being funny?”

“No. I wouldn’t try that again.”

“Can’t you just leave me in peace for the last moments of this vacation?”

“No,” Ewell said, his voice quiet and deeply unhappy. “I can’t do that. I can’t leave you alone. Especially not during our last moments together. I keep thinking that I’ll never see you again. That you’ll leave angry at me, angry at this week. I have to keep trying to help you.”

Alice turned to him, stopped walking, stood directly in front of him, grabbed his shoulders in both her hands and shook him as if to wake him up. “There is no way that you can help me!” she exclaimed. “Don’t you understand?” She trembled with anger and frustration.

“I’m sorry,” Ewell whispered. “I’m sorry for what I said. I didn’t mean to hurt you.”

BACK AT THE INN, they were changing for dinner. Standing in her underwear in front of the mirror, Alice stared at her face: “Too dark,” she said. “Probably I’ve given myself melanoma. The perfect end to a glorious week, right?”

“It has been a glorious week,” Ewell insisted. He sat on the bed with one long skinny leg folded beneath him. “Just today hasn’t been glorious.” Alice shook her head and sighed. Ewell buried his head in his hands.

Ewell tried to say a few more nice things to her, reassuring things, that he wanted to be here in the sad times and the good, to share her unhappiness as well as her joy; and finally, he thought, either she had begun to understand his message or she’d decided that she could spare some pity for him. She turned and looked at him, and her body relaxed, the muscles in her face loosened. She walked over to him, gently touched a lock of his short blond hair. Her eyes were once again the eyes of the woman he loved, and she smiled a little smile. “I must be treating you just terribly,” she said. “I’m sorry.” She wrapped her arms around him, and he held her tightly. He ran his fingers over her naked skin, and he did not know that it would be for the very last time. She kissed his ear. “I don’t mean to take this out on you,” she whispered. “Just forgive me, okay? Let’s forget about all our problems, and let’s never fight again. Okay?”

AS THEY WALKED TOGETHER to dinner, he could not utter a sentence or a phrase or even a word that did not anger her in some way. “You’re annoying me, Ewell,” she sighed, before they’d reached the restaurant. She started to turn back.

“Where are you going?”

“I’m moving to the other inn,” she said. Her words were lost in the wind, but he understood what she was saying even without hearing her speak. She began to walk quickly away from him, kicking up pebbles and dust with her little feet.

“Alice!” he shouted. When she did not stop, he screamed, “I love you!” and then she turned around. From a few yards away, he could see tears in her eyes. He shouted again to her, the same thing in his own language. “Don’t you know how hard that is to say to you, now!” he hollered, near tears himself. “I’ll do anything to stop you from going!”

Alice just shook her head, and she turned away, and she vanished over the top of the hill. Ewell could only think that this person who didn’t love him, this person full of anger and unshakable and deep unhappiness was not Alice; Alice, the real Alice, was the girl who had rolled over and smiled at him in the bright sunshine.

WHEN ALICE RETURNED TO NEW YORK, she developed her film, five rolls. All the pictures were underexposed to the point of ruin except, strangely, her photograph of Ewell’s penis, which was sharp and clear and, in its own way, rather artistic. At home, Alice smiled for a moment at the memory, then she sealed the picture in an envelope and tossed it into the bottom of a drawer.

FOR THE NEXT FEW MONTHS, Ewell sent Alice letters regularly; he even called her twice and left messages —once on her home machine, and once with her assistant. But Alice did not call back. Then one day, he called her office, and the phone had been disconnected, and he called her home, and he received the same recorded message. He gave up hope. Whenever Ewell thought about the week he had spent with her, he found himself convinced that he had met and lost the woman he was destined to love. For the rest of her life, when Alice thought of that week, she would remember the frantic 5 a.m. phone call from her assistant, she would remember her life falling apart, and if she thought of Ewell at all, she would remember only his annoyingly feckless efforts to cheer her during the final day of their holiday, and this would confirm for her how terribly wrong their match had been from the very start. She would not remember that she had almost offered to liquidate her business, move to Scandinavia with her million bucks, learn his language, whatever it was, and do whatever it was people did over there. Was his country in Scandinavia? she had wondered. Was he Scandinavian?

What countries were in Scandinavia? Holland —she was sure of that. She’d learned that in 8th grade. And probably Germany. Her mind had wandered. She would never remember how genuinely blissful she had felt entertaining the fantasy of committing her life to Ewell. Some years later, busy planning her wedding to Blake Maurow, a rich man rather older than she, and packing her belongings to move in with her future husband in his castle in the sky, Alice would take care to retrieve her photograph of Ewell’s crotch. Purely as a defensive measure, with no particular animosity to speak of, she would rip the picture into dozens of pieces, cut up the negative, and throw it all away.

Ewell married as well, to a woman named Marja who had once been his friend, a friend he’d known from infancy and who as an adult consoled him over his loss of Alice, who helped him out of his depression during the course of many months. A librarian at the local library in the town where Ewell was born. An unexciting turn of events, but, to Ewell, a comforting one. Still, as he walked down the aisle, Alice’s spirited laugh echoed in the spring air. A few years later, he learned that Alice had written a novel, a slim mystery book about a plucky single woman who solved crimes with the latest technology. It was not very successful in America, so it was never translated for Ewell’s country. He had to shell out a lot of money to import the book, and he slogged carefully through it three times, looking for some depiction however slight, or even some small residue, of the life they had lived together during their brief week in love. One of the police detectives, a good guy, was “lanky,” Ewell noticed, and blond, and had “a laugh so exuberant and startling that it scared away city-hardened pigeons.” The main character, Andrea, who bore a close resemblance to Alice’s idealization of herself, never fell in love with this police detective, but she liked him okay, and for this Ewell was tremendously grateful.

HE WOULD SEE HER ONLY ONE MORE TIME in his life, quite a while later, in New York. The reunion, as it turned out, would not be as he had imagined it. Nevertheless, for the rest of his life, whenever he would smile at a joke, he would wonder what Alice would have thought of that joke; whenever he would have a problem, he would wonder what Alice’s advice would have been. Marja’s counsel and companionship would seem always to suffer in comparison to the unknown ideal that Alice might have offered. But for that lingering sense of loss, he would believe that his marriage was otherwise a happy one; after his wife’s death sixty years later, he would realize that he did not know if Marja would have agreed.

^^^

Alon Preiss is the author of In Love With Alice (2017), from which this excerpt is taken. Available NOW from Amazon, Barnes & Noble or from ANY BOOKSTORE IN ANY TOWN OR CITY IN AMERICA

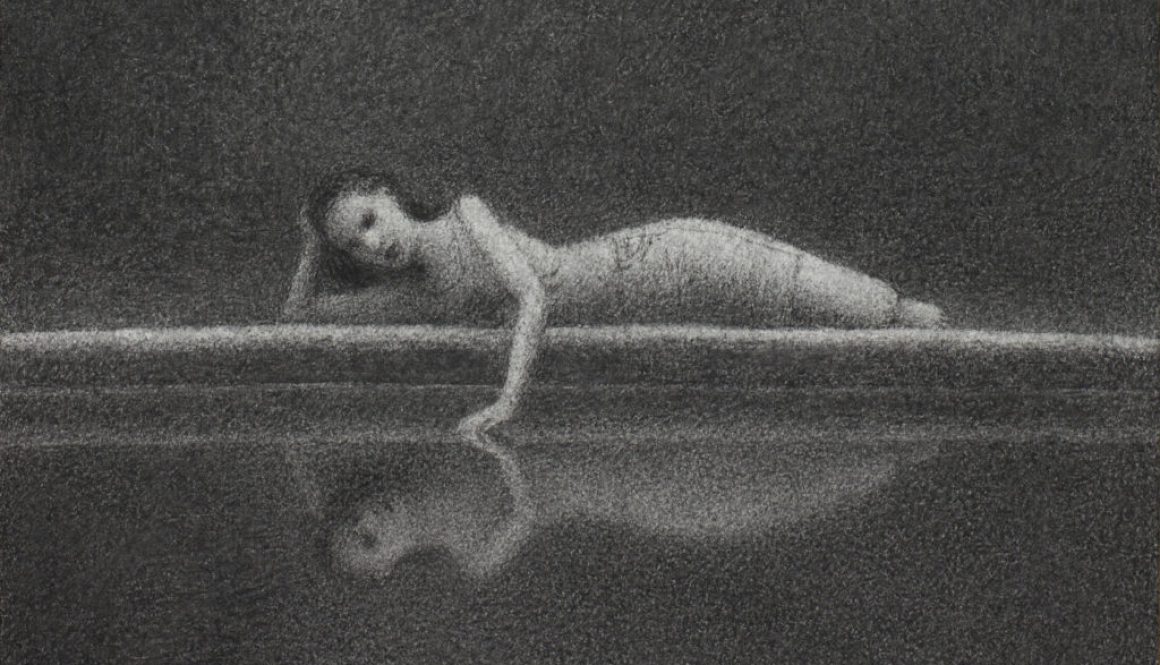

Illustration “Vigil 6,” by Aron Wiesenfeld.