Memories of Palestine before Israel: The Shlemihl

[Another in our series of sketches intended to demonstrate the existence and perseverence of both Palestinians and Jews in the land of Palestine before the existence of Israel, and well before the current hostilities. This is the second reminiscence by Bernard Drachman, from his 1905 book, From the Heart of Israel: Jewish Tales and Types. Read more here; more to come.]

Novo-Kaidansk was a most shlemihlig sort of place, and Yerachmiel Sendorowitz was the most shlemihlig of all its inhabitants.

Indeed, his character as such was so pronounced and universally known that he was seldom referred to by his proper cognomen, but usually spoken of as “Yerachmiel Shlemihl,” or, in shorter form, “the Shlemihl.” For the benefit of those of my readers who are not familiar with the Judæo-German idiom, I will explain that the noun “Shlemihl” is generally supposed to be a corruption of the first name of Shelumiel ben Zuri-shaddai, one of the princes of Israel in the wilderness, of whom Heine has sung, and who, according to Jewish tradition, was a most awkward sort of fellow, who was continually getting into all sorts of scrapes.

The noun “Schlemihl,” accordingly, signifies an aggravated sort of ne’er-do-well, a hopeless incapable; and the adjective derived therefrom is synonymous with all that is utterly unprogressive and wretched.

Both Novo-Kaidansk and Yerachmiel Sendorowitz were deserving of these appellations in fullest measure. The town was a collection of miserable huts and shanties, irregularly scattered over the dull expanse of a Lithuanian plain, with unpaved streets that were ankle-deep in dust most of the summer, and knee-deep in mud and slush and snow most of the winter.

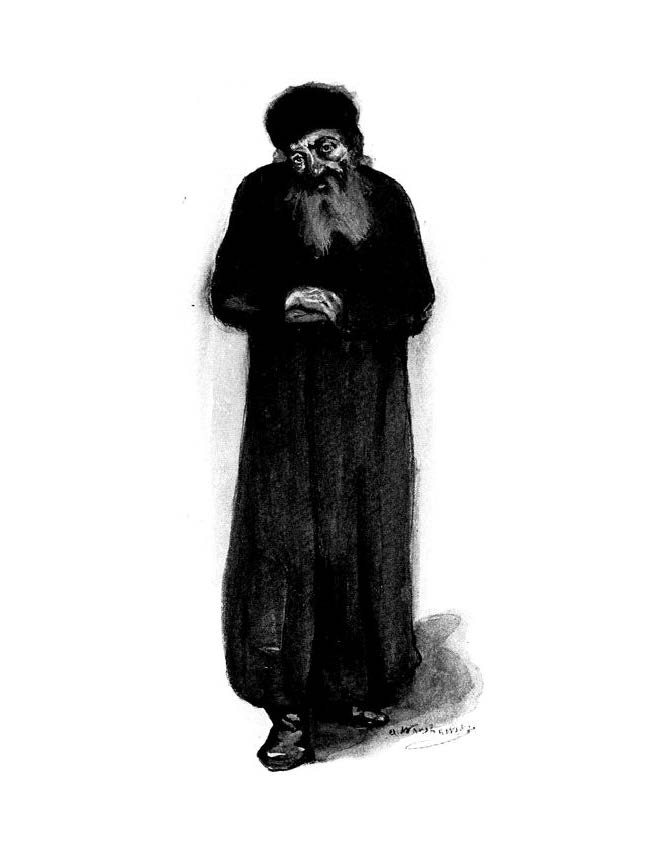

The man was a woe-begone specimen of humanity, with hungry eyes gazing at you out of a careworn, furrowed countenance, the lower part of which was surrounded by a neglected-looking, reddish beard; clad in an aged suit of many colors—a man who was ready to do any and every work for a few kopecks, and who was rarely so fortunate as to see a whole rouble. He was not a bad sort of fellow at all, nor stupid. On the contrary, he had somewhat of a smattering of Hebrew education, and he endured with patience the unceasing chidings and naggings of his wife Shprinze, who, despite the auspicious significance of her name—a Yiddish corruption of the melodious Spanish appellation Esperanza—Hope—and thus also a far-off reminder of the sojourn of the children of Israel in the beautiful Iberian peninsula—did nothing to inspire the spouse of her bosom with courage or confidence, but was enough to break down the resolution of any man.

He was never known to answer her revilings with a single harsh word. No doubt much of his patience was due to his knowledge of the fact that Shprinze had ample provocation, for, whatever might have been the reason, Yerachmiel simply could not earn a living. But, though Shprinze had provocation for her ill-temper, justification she had none. Yerachmiel did the very best he could, and it was not his fault but only the cruelty of unfeeling fate which prevented him from extracting even “bread of adversity and water of affliction” from the world.

He tried to earn a little by being a porter or burden-bearer for one of the merchants of the town at very scanty wages, but just as he was about to get the place, along came a younger and stronger man and offered to do the work for even less. Needless to say, the latter was selected. He thought he could earn his livelihood by being a Mithassek, that is to say, one who watches at the bed of the dead and performs the funeral ablutions and rites; but it was provokingly healthy that season. No one died for a long time; and when at last the angel of death did claim one of the Hebrew residents of Novo-Kaidansk—a wealthy Baal Ha-Bayith he was, too, whose family always paid liberally for all services rendered to any of its members—it just happened that they had a poor relative, an aged man of greater learning and stricter piety than Yerachmiel; and so, of course, he was preferred, and Yerachmiel was not considered at all.

At one time he dealt in fruit, purchasing a small stock with a sum of money which a pitying philanthropist had given him in order to set him up in business; but the demand for fruit was very slack just then, and in a short time Yerachmiel decided to retire from that line of commerce with the capital which he had originally possessed, that is to say, nothing. He made a dozen other attempts to coax the unwilling world into providing him with sustenance, but each attempt ended with the same result—failure, and caused him to sink appreciably lower in the estimation of Shprinze, whose temper grew bitterer and whose tongue sharper with every new proof of her husband’s Shlemihligkeit.

In fact, the term Shlemihl no longer harmonized with her conception of her husband’s worthlessness; it was too mild, too utterly inadequate. She began to address him by no other term than Shlamazzalnik, that is, one doomed and predestined to perpetual misfortune; and soon the neighbors and the other townspeople, and even the children on the streets, took up the cry, and “Yerachmiel Shlamazzalnik” resounded from one end to the other of the dusty highways of Novo-Kaidansk whenever the poor fellow made his appearance.

Poor Yerachmiel! He used to console himself by saying that he was the equal in some respects of the great Ibn Ezra, the renowned Hebrew exegete and poet of the Middle Ages, for the latter was also an incurable Shlemihl and Shlamazzalnik.

Yerachmiel used to think he was reading of his own experiences when he read the complaint of Ibn Ezra: “Were I to deal in candles, The sun would shine alway; And if ’twere shrouds I’d handle, Then death would pass away.”

But poetry, though it may be a good consoler, is a poor substitute for substantial food and the other requisites of a comfortable life; and so Yerachmiel was not entirely satisfied with his lot, even though the great Ibn Ezra was a companion in misfortune.

Finding that his attempts to earn a living by work were not crowned with success, Yerachmiel did what other unsuccessful persons have done under similar circumstances—he took to religion. He became an assiduous attendant at the local Beth Hammidrash, was present at all services, morning, afternoon, and evening, and remained in the sacred edifice during the greater part of the day and night. He would pray with great fervor, particularly the “prayer for sustenance” at the end of the morning service, would listen attentively to the rabbi or the other learned Talmudists expounding the Holy Law, and would sometimes try to learn a little himself from some of the bulky tomes.

He was, no doubt, sincere in his new-found fervor, but candor impels the statement that one of the motives of his fondness for the sacred place was a desire to have a refuge in which the sharp tongue of Shprinze could not reach him; and another was a desire to participate in the doles which were distributed on certain occasions, such as the beginnings of months or the memorial days of the death of the parents of well-to-do members to the poor persons who regularly attended. In this way he managed to exist in a precarious fashion, at least without being a burden to his wife; for whenever he had a little money he gave it to her, and when he had none he simply did not eat. It is true, he was sometimes obliged to go without food or with next to none for several days at a time; but, like all other things, semi-starvation becomes a habit, and Yerachmiel was so used to it he did not even complain.

One afternoon he was poring over one of the volumes of the Talmud, trying to interest himself in a particularly intricate disputation between Abaye and Raba, and thus forget the unidealistic fact that he had not eaten a substantial meal in three days, and that there were no visible prospects of obtaining any in the near future. He had fallen into a light doze, and was just dreaming that he had been invited by the Parnass to take dinner with him on the Sabbath, and that the Sabbath goose, juicy and savory and appetizing, had just been carried to the table, when he was aroused by a hearty whack on his shoulders and a loud voice exclaiming, in boisterous though friendly tones, “Wake up, old Chaver! What are you doing here?”

Yerachmiel awoke with a start. The vision of savory goose disappeared into thin air, and he was about to protest angrily against the rude disturbance of his entrancing dream when he recognized that the man who stood before him with a broad smile upon his countenance was none other than Shmulke Aronowitz, his old-time friend and boyhood comrade.

It was Shmulke, sure enough, but strangely altered. He was dressed in an elegant suit of foreign make; his hair and beard were closely trimmed, and his whole appearance, including his ruddy countenance and his cheerful smile, indicated prosperity. All of these characteristics were strange enough in Novo-Kaidansk, heaven knows, but they were hardly to be wondered at in Shmulke, who had emigrated to America some twenty years previously and had amassed wealth in the liquor business in the classic vicinity of Baxter Street, New York. He had Americanized his cognomen into Samuel Aarons, and had incidentally acquired local fame by pugilistic ability so that he was sometimes referred to as “Sam, the Hebrew slugger.”

He was now on a visit to his native town, where his parents still resided, and was unfeignedly glad to see Yerachmiel, who had been a real chum to him in boyhood days. The latter sat gazing dazedly at his old friend for a few moments, utterly unable to speak, so overwhelmed was he by the unexpected sight and also by the manifest contrast between his own condition and that of his friend.

Shmulke recalled him to himself. “Come, come, old comrade,” he said with good-humored impatience. “Don’t sit staring at me as though I were a curiosity in a circus. Speak out and tell me how you are getting on.” Thus encouraged, Yerachmiel lost no time in pouring his sad story into the ears of his friend. Shmulke listened attentively until the tale was all told, including the present hunger and the dream goose, and then said: “That is too bad, Yerachmiel. I am really sorry that you are so unfortunate. Come with me now to the inn of Reb Yankele, where, if you can’t get the roast goose of which I deprived you, at least you can get something to eat, and there we can consult as to what can be done for you.” Yerachmiel complied with alacrity.

Reb Yankele was more than surprised at the unexpected apparition of Yerachmiel the Shlemihl, who had never in all his life been rich enough to be a guest at the Kretchm, although he had been glad to get an occasional meal or drink there in return for odd jobs, boldly entering his establishment as the companion of a manifestly prosperous Deitch. He stepped forward with an obsequious bow and a deferential “What do the gentlemen wish?”

“The best your house has of food and drink,” answered Shmulke, “and be quick about it. A rouble or two more or less makes no difference.”

Thus encouraged the innkeeper performed his task with alacrity; and in a few minutes Shmulke and Yerachmiel were sitting down before a very fair meal, consisting of beet soup, roast chicken, boiled potatoes, black bread, onions sliced in vinegar, and a large bottle of vodka. Yerachmiel almost imagined himself in Gan Eden, and was convinced that if dreams were not prophetic, they were certainly closely akin to prophecy. The roast chicken, if not equal in quality to the dream goose, was not much inferior; and the vodka, while undoubtedly not as good as the wine which is stored up for the righteous since creation’s dawn, was yet abundantly satisfying to a poor sinner in the cheerless present.

Shmulke watched Yerachmiel’s enjoyment of the meal with a quiet smile of satisfaction, and said to him: “What is the best way to provide you with a permanent parnoso?” Yerachmiel did not exactly know. He suggested half a dozen different sorts of business, from banker to butcher, but was most inclined to favor the occupation of innkeeper, of whose delights he had just had emphatic demonstration.

Shmulke rejected all these propositions with scorn. “To tell you the truth,” he said, “I don’t believe you could succeed at anything in Russia. You are too much of a Shlemihl, and you could never get along without some one to look after you. What do you say to going with me to America? I would set you up in business and help you along with my advice.”

The magnificence, as well as the unexpectedness, of this proposal fairly took Yerachmiel’s breath away. Indeed, it made him feel a little faint. He did not really want to go to America. He admired America as a land of extraordinary and incomprehensible prosperity; but he also feared it as a land which corrupted Jewish piety, and made the holy people faithless to their ancient heritage.

He would rather have remained in his native place and continued to live in his accustomed manner could he have been assured of even the most modest sustenance. But in his heart he knew that Shmulke had spoken the truth; that he was too much of a Shlemihl to succeed without friendly aid and sympathetic guidance, and that he could not expect to receive those from any one except the old friend of his youth. He therefore murmured a confused assent, adding, however, faintly that he was afraid Shprinze might not be willing to have her husband leave her and go to so distant a land.

“Don’t worry about that, old friend,” said Shmulke, with a broad smile. “I’ll guarantee that she will not put any obstacles in the way of her own prosperity. And now that you have agreed, we will go and see her at once.”

Shmulke was right. Shprinze assented at once to Shmulke’s proposition, which was that he would take Yerachmiel to America and assist him to become self-supporting, that he would provide her with sufficient money to maintain her for several months until Yerachmiel would probably be able to send her of his own earnings; and that if Yerachmiel proved unable to adapt himself to the conditions of America and find his way in his new home, at the end of three years he, Shmulke, would send him back to his native place with a substantial gift. Indeed, her assent was so willing, and given with such manifest pleasure, that it jarred disagreeably upon Yerachmiel, and was not altogether pleasing even to Shmulke.

Thus did Yerachmiel Sendorowitz become a resident and a respected citizen of the metropolis of America. It is not necessary to enter into the details of his career in the New World, which did not differ essentially from that of many of his Russian Jewish compatriots.

At first he was a peddler, Shmulke providing him with suitable goods and initiating him into the mysteries of the profession. He did not fail. The mysterious something in the American atmosphere which confers energy and shrewdness and practical sense seemed to be even more potent than usual in his case. This may have been due to the fact that the Shlemihligkeit, which had hitherto been his distinguishing characteristic, had been more apparent than real, and that he had really possessed innate qualities of courage and astuteness which only had lacked the opportunity of manifesting themselves.

However that may have been, he certainly became a different man under the invigorating influence of America. He toiled early and late with untiring assiduity and industry; he purchased his little articles of merchandise wisely and sold prudently. In six months he had developed into a customer peddler, and no longer wandered through the streets with a pack upon his back, but went with samples only to the numerous customers whose friendship and trade he had gained, and received their orders.

A year later he had given this up also, and was the proud and happy possessor of a peddler’s supply store in one of the little streets which abut on the main thoroughfare of the Jewish East Side, Canal Street, and had purchased a tenement house. Success even affected his personal appearance favorably. The old slouchy, unkempt, ne’er-do-well, with the hungry eyes and hopeless air, had disappeared forever, and in his stead had come a bright, alert, neat, active man. Yerachmiel the Shlemihl had given way to Mr. Sendorowitz, the prosperous wholesale merchant and real-estate owner.

Nor had he failed to keep his promises to Shprinze. He wrote to her regularly, every week, telling her in detail and with great pride about his doings and his successes, not failing either to give due credit to Shmulke for the large share which the latter had had in bringing about these gratifying results, and always inquiring solicitously about her health and welfare.

Once a month he sent her money, at first only a few roubles, afterward larger sums, but always sufficient to enable her to live in proper comfort in the little Russian town of her residence. He often wrote her, too, of his intention to go out and take her to his new home as soon as business would permit, she having expressed a strong aversion to crossing “the great sea” alone. In all this he was thoroughly sincere, for he was naturally the soul of honor, and really loved his wife in a simple, unreflecting way, despite the slight cause she had ever given him for affection. Besides, his Talmudic studies had given him a clear conviction that a Jewish husband was under many obligations to his wife; but his ideas of the counter duties of wife to husband were much less distinct.

Despite the slight demands which he made upon the conjugal sentiment of his life partner, he had, however, to confess to himself that the letters of Shprinze were not satisfactory. They were excessively brief, not very frequent, expressed very little interest in his personal welfare or his doings, and invariably contained a demand for a larger amount of money. Yerachmiel tried to obey the rabbinical precept, “Judge every one leniently,” and to find excuses for Shprinze’s unsympathetic demeanor.

He told himself that women are naturally inclined to scold, and that Shprinze was merely following the rule of her sex; that she did not put full faith in his tales of prosperity, and was demanding money as a test of their truth; that women are naturally less expressive of the affection they feel than are men, and a half-dozen other excuses for her apparent coldness and mercenariness. But none of these excuses seemed really adequate, and gradually Yerachmiel found a great dissatisfaction with the conduct of his wife toward him rising in his breast.

Finally, a most painful question began to torture him. “Did Shprinze love him at all, or was her interest in him purely mercenary, and limited to the material benefits which she could derive from him?”

Simple-minded as Yerachmiel was in worldly things, untutored in romantic concepts and affairs of the heart, his whole nature revolted against the idea of marital relations with a woman in whose soul burned no flame of love for him as her husband. But how could he ascertain the truth; how find out whether his wife really loved him or not?

Gradually a plan matured in his mind. He did not permit Shprinze to have any inkling of the doubts and the conflicting emotions by which he was agitated. He wrote her as frequently and regularly as hitherto, and sent her monthly remittances of money with unfailing punctuality. After some five years of absence he wrote her that he had found it at last possible to withdraw his constant personal attention from business for a few months, and that he would come out and take her with him to his new home in America. When Shprinze received this letter it did not fill her with the joy which the prospect of reunion with a beloved and long-absent husband might be expected to inspire in the heart of an affectionate and devoted wife. She would have preferred the indefinite continuance of the condition which had now lasted upward of five years, and which she had found very agreeable.

It had been very pleasant to receive constant remittances of money, to live in comfort and ease, and to be looked up to on all sides as the fortunate and happy one. When she had entered the women’s gallery in the synagogue all the women had hastened to make way for her with the utmost deference; and many a highly esteemed Baal Ha-bayis had looked upon her with favor, and would not have spurned to ask her hand in marriage if her incumbrance on the other side of the Atlantic would only have been good enough to make a polite exit for a better world, leaving her a substantial fortune in American dollars.

And now all this was to cease; and she must leave her native place for a strange land, and live again with one whom in her heart she still despised as a Shlemihl, despite his unexpected good fortune in the New World. Besides, she had a dim presentiment of evil, a feeling that the advent of Yerachmiel meant some undesirable change in her tide of fortune, why or what she could not think. At last a despatch came from Yerachmiel, informing her that he was in Hamburg, and would reach Novo-Kaidansk with the train due at such and such an hour. At the appointed hour she was at the station, accompanied by quite a throng of Jewish townsfolk bent on giving their long-absent townsman a hearty welcome.

Speculation was rife as to his appearance. Some thought that his long absence in a foreign land would have removed his Jewish looks; that he would have shaved off his beard and assumed in every way the appearance of the Gentile. Others thought such a thing impossible of Yerachmiel Sendorowitz; that he was far too pious and God-fearing to fall away so utterly from Jewish ways, and that the only change probable was that he would be elegantly attired in fine clothing, and would show in his prosperous and beaming aspect the possession of much America-gained wealth.

The grimy train, drawn by the ugly, soot-covered locomotive, swept into the low-roofed Russian station. The swarm of passengers, of all kinds and degrees, flowed from the narrow openings of the cars; and then a shock came over the waiting throng. From amidst the crowd of passengers emerged one who was unmistakably Yerachmiel; and, horrible to relate, the Yerachmiel of old, Yerachmiel the Schlemihl. To be sure, he was not exactly the same in appearance as of old, for the hat and suit that he wore were of American make; but they were shabby and dusty, and ill suited to a prosperous man. His hair and beard were unkempt and neglected, and his face bore an expression of anxiety and care.

All were surprised and shocked; but the most pitiably shocked of all was Shprinze.

Yerachmiel at once recognized his townsmen and his wife, and advanced with a sort of wan smile to greet them. The former, of course, returned his greetings, and inquired how he had fared in America; but their embarrassment was only too manifest, and cutting short his answers to them, Yerachmiel turned to his wife, who had been standing all the while as if petrified, and said: “Come, Shprinze, let us go home.”

Mechanically she led him to her home. Hardly had the door of the little dwelling closed behind them when all the animation and energy which had left Shprinze when she beheld her spouse in such unexpected and unwelcome guise suddenly returned.

“What is the meaning of all this?” she demanded fiercely, while flames of wrath blazed from her piercing eyes. “Why do you come to me from America looking like a beggar and a ragged saint fresh from the benches of the Beth-Hammidrash instead of a prosperous New York merchant, as you had made us all believe you had become? Was it all a lie, your oft-repeated tale of your success in business and your progress? Did you steal the money you sent me, and have you fled from the officers of the law, who, perhaps, are after you now? Oh, you are still the same old Shlemihl, the same old goodfor-nothing! Why did the Most High curse me by making me your wife?”

“My dear Shprinze, do not rave so!” expostulated Yerachmiel. “How can you say such things before you have heard any explanation from me? I am not a liar nor a Shlemihl. Whatever I wrote you about my business success in America was strictly true; and the money I sent you was my own, and all honestly earned. I have come to take you with me to America; and I already have the steamship tickets for us both, and plenty of money for railroad fare and necessary expenses.”

“Then why are you dressed so shabbily?” continued Shprinze, with undiminished fierceness; “and why do you look so down-hearted? Is that the appearance and the bearing suitable to a wealthy merchant, such as you have claimed to be?”

“I suppose I am not very particular about my appearance,” answered Yerachmiel; “and then, I admit, I have had considerable trouble and losses in business lately, and that may have given me a worried look. But what need that concern you? I have learned the art of getting on in America, and I do not fear but that I shall soon be able to recover whatever I have lost. In the mean while I am here. I am your husband, and I ask you to come and make your home with me.”

“You are mechulleh,” said Shprinze, suspicion gazing out of every line of her excited countenance. “I can understand from what you admit that you have lost all you had, and you want me to share your poverty, or perhaps to give you the money that I have saved from what you sent me! I shall not do it! I do not want to go with you! Give me a Get. I do not want to be the wife of such a Shlemihl.”

Yerachmiel’s pale face became fiery red when he heard these harsh and heartless words; but again he endeavored to bring his wife to a better frame of mind.

“Shprinze,” he said in appealing tones that might have melted a heart of stone, “is this my welcome home? Have I deserved this of you? Have I not always been faithful to you, even when I was a poor Shlemihl in this town, and did I not give you every kopeck I earned? Did I not send you money abundantly from America? You may trust me. I still have the means to support my wife, and therefore I again ask you to come with me to my home, as beseems a good and true wife in Israel.”

“I will believe you are not mechulleh,” said Shprinze, in a tone of calculating shrewdness, “if you will give me a thousand roubles now. If you do that I will go with you.”

“That I shall not do,” said Yerachmiel, a manly anger getting the better of his usual extreme mildness. “I do not need to buy my wife. Have you no love for me at all? I ask you to go with me because I can support you; and as a wife you can ask no more.”

“Then I see you are mechulleh,” answered Shprinze, “and I will not go. Divorce me, I say; give me a Get. I want none of you or your money. All I want is a Get.”

Again and again did Yerachmiel appeal to Shprinze’s better nature. It was of no avail. She persisted in her demand and could not be induced to alter it. Seeing that her determination was unalterable and that her one wish was to be separated from him, Yerachmiel, although according to the Jewish religious law he could have refused to consent to the desired divorce and thus have effectually baffled any other matrimonial plans that Shprinze might have entertained, decided to accede to her wishes.

“I shall do as you ask, hard-hearted and ungrateful woman,” he said; “for even now that you treat me thus cruelly I wish you no evil. But one thing I must tell you. In order to show that this divorce is not in accordance with my wish, I shall pay neither the rabbi, nor the scribe, nor any of the other expenses. Whatever outlay there is you must defray. Thus shall all know that you are the one who seeks to undo the bond that has bound us together these many years, but that I am satisfied to keep you as my lawful, wedded wife.”

Shprinze eagerly agreed to this; and having further agreed that they should meet on the morrow in the house of Rabbi Israel, the spiritual guide of the Jewish community of the town, they separated, Yerachmiel leaving the house without word of farewell.

Great was the surprise of Reb Yankele, the innkeeper, when Yerachmiel, whom he had assisted in welcoming at the railroad station a few hours previously, entered the inn and gloomily inquired whether he could be accommodated with food and lodging for the night. He wondered greatly why Yerachmiel was not staying in his own home on the first night after his arrival from a distant land; but the latter volunteered no explanation, and Reb Yankele did not venture to ask for any.

However, he did not need to remain long in ignorance. No sooner had Yerachmiel left his wife’s house than Shprinze rushed to the nearest female neighbor and told her the news, adding many dreadful details about the repulsiveness of Yerachmiel’s appearance, his poverty, and his hopeless Shlemihligkeit; adding, however, that in spite of all she must be grateful to him for his willingness to grant her the divorce she craved, and assuring her (the neighbor) of her unutterable joy at the prospect of being at last free from an incurable Shlemihl and Shlamazzalnik.

The neighbor, of course, had no more imperative duty to perform than to put her shawl over her head and rush to communicate to her nearest neighbor the news, still fresh and hot, of the impending divorce of Yerachmiel and Shprinze Sendorowitz. In this way not two hours had passed before the whole Kehillah of Novo-Kaidansk had learned the news. Reb Yankele had learned why Yerachmiel was his guest; and even Rabbi Israel had been informed, at evening service in the synagogue, of the function which he was to be asked to perform on the morrow.

At nine the next morning Yerachmiel and Shprinze were in the large front room in the rabbi’s dwelling, which served as his office, and whither repaired whosoever in Novo-Kaidansk had a religious question to ask or a ceremony to be performed, or that was in need of spiritual counsel or guidance of any kind. Shprinze was gayly attired, and chattered constantly with a group of female acquaintances by whom she was surrounded. She was in high spirits, and cast occasional contemptuous glances at Yerachmiel, who sat, moody and abstracted, in a corner and spoke to no one.

Besides these the room was crowded with the most notable members of the congregation, drawn hither by the exceptional interest which this extraordinary case had aroused. The side door opened, and a hush fell upon the assembly as the venerable Rabbi Israel, accompanied by two coadjutor rabbis and several other persons who were to take part in the solemn function of pronouncing the divorce, entered and took their places in seats which had been reserved for their occupancy, behind long tables at the head of the room.

The Shammas then asked in a loud voice whether there was any one present who desired to consult the Beth Din on any matter.

At this Yerachmiel arose, and, addressing Rabbi Israel, said: “Venerable rabbi, I desire to divorce my wife, Shprinze, daughter of Moses; and I request of you to ordain the issuing of such a divorce, according to the law of Moses and Israel.”

“I hear your request with sorrow,” said the rabbi, while an expression of pain passed over his venerable features. “Is it the desire of your wife also that your marriage be dissolved?”

Yerachmiel bent his head in assent; and the Shammas, in response to a motion of the rabbi’s hand, called in a loud voice: “Shprinze, daughter of Moses, step forward.”

Shprinze did so, and the rabbi put to her the question whether she consented to the dissolution of her marriage to Yerachmiel, son of Isaac, to which she responded with a loud and distinct “Yes.”

Summoning them both before him, the rabbi now addressed to them a long and earnest plea to give up their intention of divorce. He pointed out to them that, although the holy Torah permitted the dissolution of a marriage which had been polluted and desecrated by gross and abominable sin, or which had grown utterly intolerable to either or both parties, and left it to their decision whether it should be dissolved; yet it did not approve, but, on the contrary, severely condemned, the tearing asunder of the holy bonds of wedlock, and that in the words of the sages the altar shed tears over husband and wife who became recreant to the covenant of their youth.

He therefore entreated them most earnestly to become reconciled to each other, and to remain faithful to the pledges which they had once taken upon each other.

To this touching plea they returned no answer. Yerachmiel gazed at the floor, his face alternately flushed and ashy pale. Shprinze gazed at the rabbi with firm eyes and shook her head in the negative.

Seeing that his efforts at reconciliation were useless, the rabbi then announced “the giving of the Get must, therefore, take place.”

These words were the signal for the commencement of the divorce ceremonial, which was now performed with all the solemn and impressive formalities with which it has been carried out since time immemorial in Israel. The rabbi appointed an expert and skilful scribe to write the bill of divorce, which must be written in strict accordance with many minute and detailed rules, the neglect or violation of any of which would render it invalid. He also designated two pious and trustworthy men, both proficient in the art of writing the square Hebrew script, to act as the official witnesses to the document.

The scribe seated himself at his desk and produced his paper, quill pen, and ink, all of them specially prepared, in accordance with fixed rules, for this purpose.

To him Yerachmiel, acting under the instruction of the rabbi, now spoke and directed him to write a bill of divorce for his wife, Shprinze, daughter of Moses. Amidst breathless silence the scribe now began to write the document which was to sunder two lives hitherto joined. The writing lasted a considerable time; and during all its continuance not a sound, save the steady scratching of the scribe’s pen, was heard, for it is strictly forbidden to make a noise of any kind while a Get is being written, lest the sound disturb the Sopher and cause him to err in some particular, thus necessitating the rewriting of the document.

At last the bill of divorce was finished and the two witnesses appended their signatures, written in the square Hebrew script, and without title of any kind. The rabbi then designated two other men of religious standing and good repute to be the official witnesses of the delivery of the Get.

Summoning Shprinze, the rabbi bade her uncover her face, which hitherto during the proceedings had been covered with a heavy veil, and said to her in solemn tones: “Shprinze, daughter of Moses, art thou willing to accept a bill of divorce from thy husband, Yerachmiel, son of Isaac?”

Shprinze responded with a firm “Yes.”

Turning to Yerachmiel, the rabbi asked him whether he still desired to divorce his wife, to which Yerachmiel answered in the affirmative.

Turning again to the woman, the rabbi said in a stern voice: “Give me thy Ketubah. Thou no longer hast any use for it.”

At this, the most feared part in the divorce ceremony, Shprinze’s face grew slightly pale; but she drew forth her marriage certificate, which she had brought along for this purpose, and gave it to the rabbi, who laid it aside, to be destroyed immediately after the completion of the divorce proceedings.

The rabbi then bade her remove her marriage ring and extend her hands to receive her bill of divorce.

Yerachmiel then took the bill of divorce, placed it in the outstretched hands of Shprinze, and said: “Behold, this is thy bill of divorce. Accept thy bill of divorce, and by it thou art released and divorced from me, and free to contract lawful marriage with any other man.”

With a few earnest words from the rabbi pointing out the duty of living their separate lives in peace and righteousness, and of avoiding in the future the sins which had led to this sorrow, the ceremony was concluded.

Yerachmiel and Shprinze were no longer man and wife. At once a clamorous buzz of conversation arose all over the room. The excitement which had been suppressed so long now burst the bonds of enforced silence and found relief in vociferous exclamations of wonderment and emphatic expressions of approval and disapproval. Some of the women congratulated Shprinze; others held aloof. The men were unanimous in their condemnation of the hard-hearted woman who had taken her husband’s money for years and then induced him, when grown poor, to give her a divorce.

The excitement was at its height, when suddenly a tremendous rap on the table drew the startled gaze of all toward the spot whence the sound had proceeded. What they saw caused a hush to fall over the assemblage. Yerachmiel stood at the side of one of the tables, his cheeks ashy pale, his eyes blazing with a furious light that no one had ever seen in them before, fiercely rapping with his cane in an effort to procure silence. As soon as his voice could be heard he began to speak.

“Jewish brethren and sisters of Novo-Kaidansk,” he said, with painfully labored yet distinct utterance. “You have come here to see Yerachmiel the Shlemihl give divorce to his wife, Shprinze. I know most of you are good people and have pitied me for being such a Shlemihl that I could not keep either my money or my wife. But, perhaps, I am not such a Shlemihl after all. I have not desired nor sought this divorce, but I have tried to find out the truth about an old wrong and to right it; and I believe I have succeeded as well as some who are considered wiser and cleverer than I. Shlemihl though I may be, I have always tried to do my duty toward my wife. Even before I went to America, when poverty and wretchedness were my lot in this town, I gave Shprinze every kopeck that I earned. From America, where God blessed me and made me prosperous, I sent her regularly all that she could properly require. But in return for this I asked wifely love. I knew that a husband must honor, cherish, and maintain his wife; and that a wife must, in true marriage, return love for love, affection for affection. Shprinze never showed the least trace of love for me. My soul hungered and thirsted for love. Shprinze gave me, at worst, bitter revilings and beratings, tongue-stabbings that pierced my soul like the thrusts of a sword; at best, cold indifference. In the beginning, when I could not, because of poverty, properly support her, I excused her.

“I said to myself that I deserved nothing better. But when from America I sent abundance of gold and loving words, and showed in every way I could that I was a true and loving husband, and when, in return for all this, I could not get an affectionate word, a loving sentence, I resolved that I would find out whether in Shprinze’s heart dwelt a spark of love for me, or whether it was only my gold she loved. The rest you know. I came here, dressed in shabby clothing, looking the olden Shlemihl. Her evil heart made her quickly conclude that I had lost my all, and without questioning me or offering, like a true wife, to share my lot, she demanded a divorce. I saw that she loved me not, that she had never been to me more than a wife in name, and to-day I have granted her wish. But let me assure her and you, friends, that she is mistaken in thinking that she has now got rid of a Shlemihl, of a poor, never succeeding unfortunate.

“She has freed herself of a successful, of a wealthy man; she has deprived herself of a splendid home in the greatest city of free America; she has deprived herself of luxury and riches, and, what is more, of the love of a man who was deeply attached to her, and who would have given his all for a kind word or a loving kiss from her lips. See, here are the presents I had brought here for her, and would have given her had she treated me rightly.”

So speaking, he drew forth a magnificent diamond necklace and a beautiful, richly ornamented gold watch and chain.

“And here is the proof that I am a man of means and no deceiver—a letter of credit on a Berlin banking-house for ten thousand marks”—and here he drew from his wallet the precious document and flourished it triumphantly yet sorrowfully before the eyes of his hearers. “As for me,” he continued, “I thank the All-Merciful that He has opened my eyes to the truth, and that He has freed me from a serpent that would only have devoured my substance, and with its icy touch have frozen my heart. Now farewell, friends, and farewell, false and heartless woman. I go to my home beyond the sea, where I shall try to forget this long, sad dream of misplaced love and cruel ingratitude and heartlessness.”

Having thus spoken, he turned and left the room. None ventured to detain him or to restrain his departure. As he went out of the door, Shprinze, who had been listening with strained attention to his words, and whose countenance had alternately flushed and paled as he spoke, rushed forward as if she would have held him back, then paused, uttered a piercing, heartrending shriek, and fell in a deathly swoon to the floor.

The cry reached the ears of Yerachmiel as he strode down the dusty street. An expression of pain crossed his features as he heard it, but he did not turn and he came not back.

^^^

Chickadee Prince Books publishes a number of books about Israel/Palestine. For more, take a look at Enough Already – A Framework For Permanent Peace in a New Palestine and Israel by Steven S. Drachman; Figs and Alligators: An American Immigrant’s Life In Israel in the 1970s and 1980s by Aaron Leibel; and Max’s Diamonds by Jay Greenfield.