LOCKING UP THE POOR

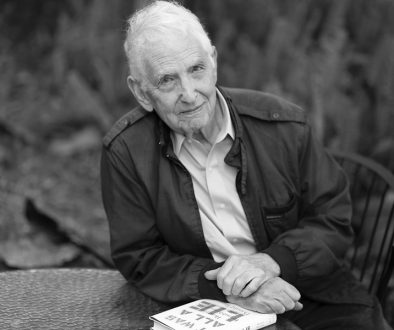

By Ed Rucker

When an individual is arrested and charged with a crime, whether they remain in custody or are released pending trial is merely a question of money. That is, whether they are able to post the monetary amount of the bail set by the court. In California, judges routinely set the dollar amount of bail by merely following a chart or schedule of bail amounts. Superior court judges in each county are required to annually prepare a uniform countywide schedule of bail for all felony and misdemeanor offenses.

Bail schedules provide standardized money bail amounts based on the offense charged and prior offenses, regardless of other characteristics of an individual defendant that might bear on the risk he or she currently presents.

These schedules, therefore, represent a one-size-fits-all approach rather than an individualized inquiry into the circumstances of each case.

Bail schedules have been criticized as undermining the judicial discretion necessary for individualized bail determinations, based on the inaccurate assumption that defendants charged with more serious offenses are more likely to flee and reoffend, thus enabling the detention of poor defendants and the release of wealthier ones who may pose greater risks.

Empirical studies points out that, “the evidence does not support the proposition that the severity of the crime has any relationship either to the tendency to flee or the likelihood of re offending.” (Karnow, Setting Bail for Public Safety(2008) According to Judge Karnow, “the most exhaustive empirical studies of bail practices in the United States” suggest instead “that the severity of the crime cannot be used as a proxy for the danger posed by the defendant if he were released on bail. Accordingly, the current practice by which judges simply follow the bail schedules is, to put it delicately, of uncertain utility.”

The practice of using bail schedules leads inevitably to the detention of some persons who would be good risks but are simply too poor to post the amount of bail required by the bail schedule. They also enable the unsupervised release of more affluent defendants who may present real risks of flight or dangerousness, who may be able to post the required amount easily and for whom the posting of bail may be simply a cost of doing ‘business as usual.’ For poor persons arrested for felonies, reliance on bail schedules amounts to a virtual presumption of incarceration.

The greater injustice of the current bail system falls on those who are innocent of the criminal charges. For example, an analysis of county jail populations in California during 2014-2015 shows that 5,584 persons were booked into the San Francisco County Jail for the mean number of five days although charges were never made against them or were dismissed, and the cost to the county of those detentions, which numbered 28,671 days, was $3,264,766.77. (Human Rights Watch, “Not in it for Justice.” (2017) The statewide statistics are not materially different. A 2015 study by the California Department of Justice shows that roughly one-third of the 1,451,441 individuals arrested for felonies in this state between 2011 and 2015, 459,9847 were never found guilty of any crime, charges were not even filed against 273,899 of them, and all but a small fraction were detained due to the inability to post the amount of bail set.(Criminal Justice Statistics Center, Cal. Dept. of Justice, Crime in California (2015).

More recently there are efforts to address the inequities of this cookie-cutter approach to pretrial detention. Last month, a District Court of Appeal in California rendered a decision in In re Humphrey that judges must take into account a defendant’s ability to pay the scheduled bail when bail is set. The court further explained that the prosecutor must convince the judge that no less restrictive alternative exists which might protect the public and assure the defendant’s reappearance in court. Such alternatives might be a release on the persons own recognizance with an enforceable order to reappear, home arrest or wearing an electronic monitor to and from their employment.

In Los Angeles County the District Attorney has issued guidelines that monetary bail will no longer be asked for in most misdemeanor cases. In the California legislature there is a Senate bill proposing to do away with money bail in California which has been endorsed by the Governor and the Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court.

Whether by judicial rule or by legislative enactment, California’s bail system appears to be on its way out.

Ed Rucker, a former defense attorney, is the author of The Inevitable Witness (Chickadee Prince Books, 2017).