Richard Williams has died: An Appreciation for an Animation Maverick

Steven S. Drachman: Years ago, I pitched an idea for a book to my agent: brilliant filmmaker spends 30 years on his masterpiece, a painstakingly elaborate animated feature film based on the legends of Aladdin. As he nears completion, the Walt Disney company steals the whole idea — plot, character design, everything, using a crew familiar with the animator’s workprint — and gets it into theaters first. Disney then buys the brilliant animator’s movie from the corporation that owns it, fires the animator, throws half of his work away and replaces it with cheap, crude cartooning from South Korea, terrible songs and horrible, snarky, Mystery Science Theater-style voiceovers, and dumps the movie into theaters during the last week of August.

To add insult to injury, Disney takes the animator’s earlier work off the market, essentially erasing him, the way Soviet dictators once did.

“I dunno,” my agent said. “You really don’t want to get on the wrong side of the Walt Disney company.”

Even back then, the mid-1990s, we knew that Walt Disney was poised to take over the world, and crossing them could hurt my such-as-it-was “career.”

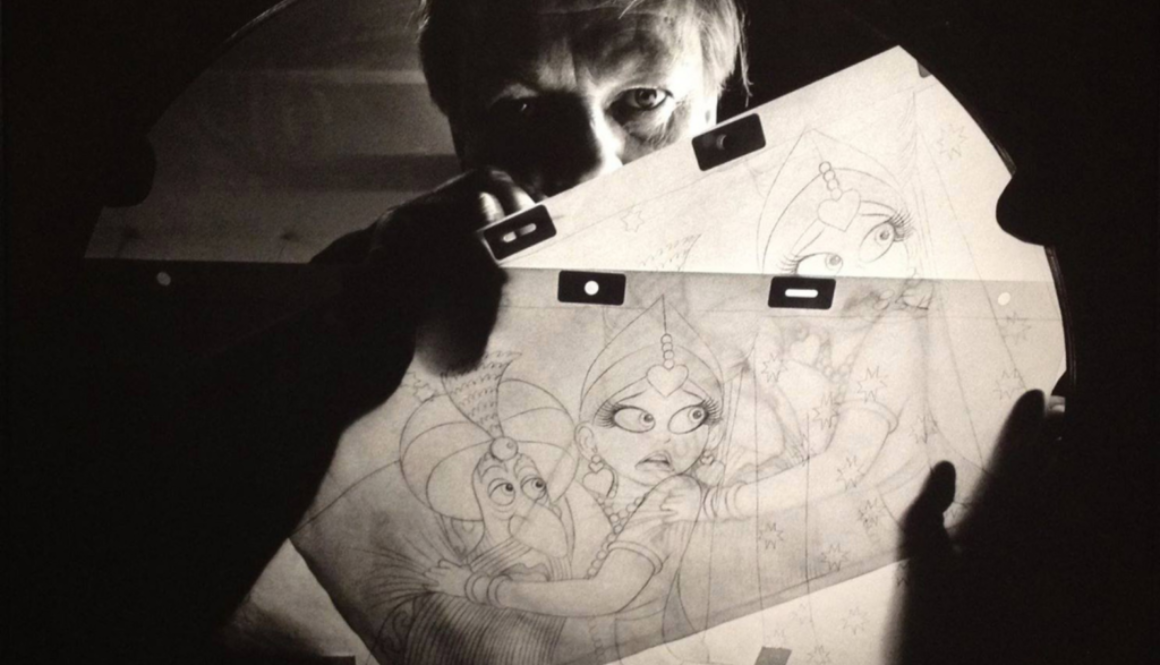

The saga of Richard Williams and his unfinished masterpiece

You may not recognize the story, but this was the saga of Richard Williams, who died yesterday at the age of 86, and his amazing opus, The Thief and the Cobbler (or, as Disney renamed its version, Arabian Knight).

My agent, the late, great Jonathan Matson, acquiesced to my idea, but only if I could get Williams to cooperate.

Williams’ handwritten response was brief and bitter. He was glad that I had enjoyed “what was left of my picture,” but he had no desire to cooperate with my book, and he indeed “ABSOLUTELY” (emphasis his own) did not want to see it, or anything like it, written.

Matson, I think, breathed a sigh of relief.

Disney may have tried to erase Williams and his work, and to crush a dogged threat to its dominance, but in its ragged demise, The Thief and the Cobbler has risen from the grave and become legendary, thanks to two young fans: Kevin Schreck, whose gripping and thrilling documentary, Persistence of Vision, told the story of the making and unmaking of Cobbler; and Garrett Gilchrist, whose Recobbled Cut reconstructed Williams’ film in a version as close to the original vision as possible, with the original soundtrack.

Disney may have tried to erase Williams and his work, and to crush a dogged threat to its dominance, but in its ragged demise, The Thief and the Cobbler has risen from the grave and become legendary, thanks to two young fans: Kevin Schreck, whose gripping and thrilling documentary, Persistence of Vision, told the story of the making and unmaking of Cobbler; and Garrett Gilchrist, whose Recobbled Cut reconstructed Williams’ film in a version as close to the original vision as possible, with the original soundtrack.

A reclusive artist

Williams remained reclusive. He didn’t cooperate with Persistence of Vision, and, as Garrett noted in an Imaginary Worlds podcast interview, he didn’t encourage the Recobbled Cut.

But let’s be grateful that Kevin and Garrett did what they did, and that, unlike me (but like the Thief), they didn’t give up. It helped that they are both talented filmmakers and knowledgeable film historians.

Now Cobbler belongs to the world. You can easily watch its colorful magnificence on the web, and you can view the Recobbled Cut from start to finish. Both Williams’ workprint and the Recobbled Cut have been viewed in theaters (including at the Museum of Modern Art), and reviewed in the media; Peter Keough raved in the Boston Phoenix and in 2016, the New York Times called it “a staggering masterpiece.” The web is filled with Cobbler articles, tributes, analyses and fan art.

The Thief and the Cobbler

Cobbler is the story of a king who discovers that everything he thought was real is an illusion (as the opening narration reveals); the speechless but heroic cobbler who wins the princess Yum Yum’s heart; the equally silent thief, who never gives up; a dark army of one-eyed invaders with a deadly war machine; and the king’s perfidious grand vizier, Zig Zag. It’s drawn “on ones,” which means that Williams created a new picture for each frame — Disney films were drawn on twos (one picture for every two frames), and even the best Japanese animation is drawn on threes. While most animated films feature moving figures in front of a static background, Williams, in many scenes, redraws the background as well, which permits Cobbler to achieve the sort of swirling camera effect only previously possible in live action films. (Today’s animated films can achieve this effect with computers, and the difference is significant.) It is artistically beautiful, hilarious and (here I will state a perhaps-controversial view) it is narratively and thematically profound. It is, simply, a great film, even in its unfinished state.

A late in life renaissance

In 2014, Williams made Prologue, a very brief and brutally violent film about an ancient battle and its aftermath. It was said to be the first chapter of a longer film based on Lysistrata. In 2018, Williams said it was the only thing he had done in his career with which he was completely happy, and that a new chapter was forthcoming that “seems to be as good, or maybe better.”

He added, “Now I have no deadline. Only the ‘death line.’ So I have time to get it right.”

Oh, yeah, by the way: Williams also did all the animation on Roger Rabbit. And the credits animation in the Pink Panther films.

He was a genius. How could he ever, ever leave us like this?

***

Full disclosure: 1) Garrett Gilchrist worked with me when Chickadee Prince Books was in its infancy; he created the logo, among other indispensable assistance. 2) I used to write for the Phoenix, and I was the one who alerted Peter Keough to Cobbler’s greatness.

Photo from the web; unknown source. Please let us know if it is yours.

Steven S. Drachman is the author of Watt O’Hugh and the Innocent Dead, which will be published by Chickadee Prince Books on September 1, 2019; it is available for pre-order in trade paperback from your favorite local independent bookstore, from Amazon and Barnes and Noble, and on Kindle.