Alon Preiss: “A Flash of Blue Sky” – what does it mean?

A few years ago, Chickadee Prince Books published the Alon Preiss novel, A Flash of Blue Sky, which was praised by Kirkus Reviews as “A debut novel that presents several intertwined stories, set against the political tumult of the rise and fall of Communism.”

The novel covered much territory – the implosion of post-Communist Russia, the war in Cambodia, anti-Semitism, the Kurdish rebellion in Turkey, and 1980s Manhattan Boomer angst, in the person of Daniel, a former artist and current New York attorney, and his wife, Natalie.

One question perplexes – what do you mean, “a flash of blue sky”?

In this excerpt from the novel, everything will be made clear.

“That’s all?” Natalie said, smiling. “That’s it? You’re worried that you’re going to die.”

“Well,” Daniel muttered. “I thought I had put it in a somewhat more thoughtful manner.”

“But Daniel,” she laughed. “That’s all you’re saying. Everyone dies, OK?” She reached out to pat him on the knee. “Don’t let a thing like that worry you.”

Daniel grumbled. “The universality of the experience isn’t something that makes me feel any better. If I knew for sure that we would all be hurtling together in free fall, as our sins are judged, then, sure, having you along would make me feel better. But knowing that my ultimate fate might be oblivion and that everyone else will also be oblivious is not comforting.” He blinked, and then he blinked again.

“But we’re atheists, darling!” Natalie insisted. “Don’t you remember? You and me, we don’t believe in God. On the plus side, we don’t have to daven, but on the minus side, life has no meaning. We’re sort of … I don’t know, I think we try to be good people, as well as we can within our own personal ethical systems, but if you’re looking for some sweeping, black-and-white, right-and-wrong, angels with harps and puffy clouds sort of philosophy … I mean, I believe in moral relativism, not the sort of – ”

“Natalie,” he said, “I wanted to sit down and work through a couple of my anxieties, not listen to a treatise on humanism.”

“Look, Danny,” she said. “For what it’s worth, you have a good job, a nice car. Can you disagree? People say, a beautiful wife, right? This is what you’ve insisted that you want, and you have it. You’re lucky.” Now she grew impatient. “I fell in love with a man who saw a beautiful painting everywhere he looked, a man with a mind like a song. Suddenly you decided to change, Daniel, and you wanted something else. I’ve had to adjust to that. Now that you’ve gotten what you set out to get – well, for goodness sake, be happy when you look at your life.”

A shadow seemed to fall across his face, but when he spoke again he just sounded more plaintive: “You can’t just tell a person to be happy, Natalie.”

“Your friend Henry died,” his wife said, “and now you realize that you will die, too? Is this news to you? Well, my friend, you remain rather unlikely to die anytime soon, but completely certain to die eventually. Exactly the same as it was before Henry died. Nothing is different. Why are you trying to pretend otherwise?”

“You’re an artist,” Daniel said. “I thought you were the person I could talk to about this.” He gestured around the room. “Look, you’re an artist whose subject matter is death.”

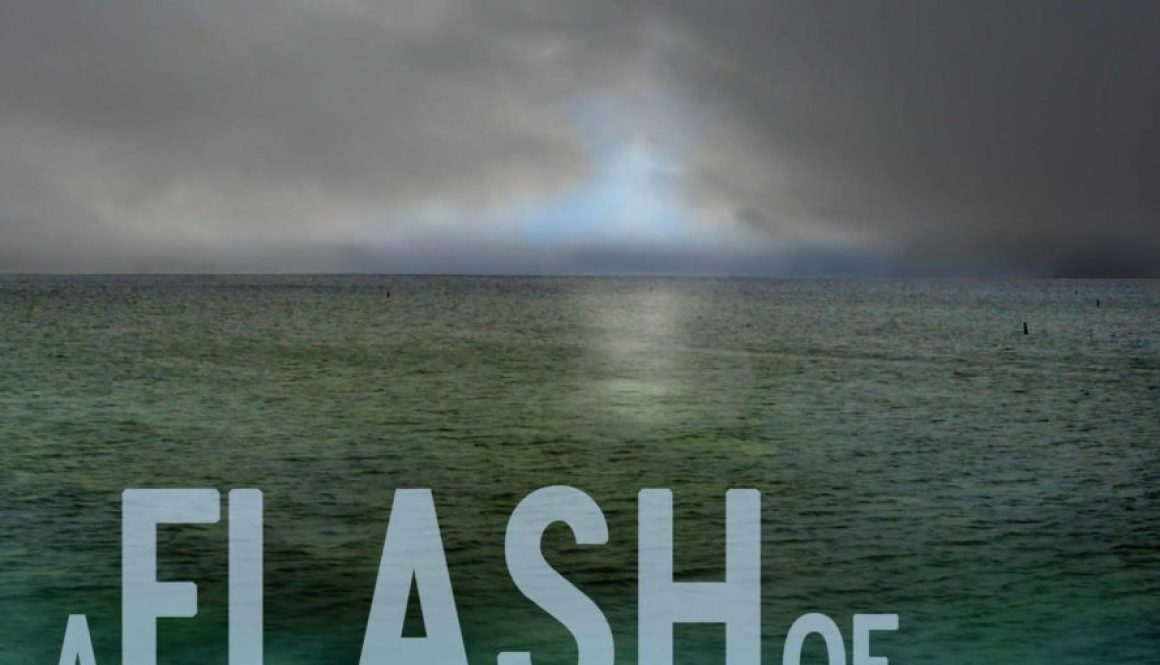

His wife shook her head. “I try to describe inhumanity and destruction and misery. That’s not what I think of when I think of death …. Look, death isn’t clouds and sunshine, and it isn’t fire and pain. It’s sort of a flat ocean, clogged with rotten algae, under a gray sky, and you just float there exactly fifty feet below the surface, and you just don’t care anymore, you can’t feel it, you can’t hear it. There are no fish, no nothing. No light, no air. You just float there, not existing at all, in this wet darkness. That’s where you were fifty years ago, and that’s where you’ll be in another fifty years. You have this little glimmer of light and air, a flash of blue sky, just a little taste of it to enjoy. So enjoy it. That’s the word for how to deal with the tiny glimpse of life you get between these two great dark bookends.”

He sat there thinking.

“Don’t try to manufacture a crisis,” she said, “just because you think you should be feeling worse than you really are. Henry was sort of a jerk; in a lonely moment, he was a momentary friend. Not ‘friend,’ I guess. Comradely colleague? Something less than a friend. Then he was gone, and quite naturally you feel less than heartbroken. You cannot mourn every death in the world. Do you know how many people die every second? And with every death, an entire world is destroyed, right? Isn’t that what they taught you in yeshiva? But who can live that way? Apathy is natural.”

He said nothing.

“Listen,” she said. “Maybe next time around you’ll be a paramecium. That sounds like fun, right? Swim around all day bumping into things. Every time you masturbate you have a new friend.”

^^^

Alon Preiss is the author of A Flash of Blue Sky (2015) and In Love With Alice (2017), which are both available from Chickadee Prince Books.