Ed Rucker: Second guessing a criminal trial

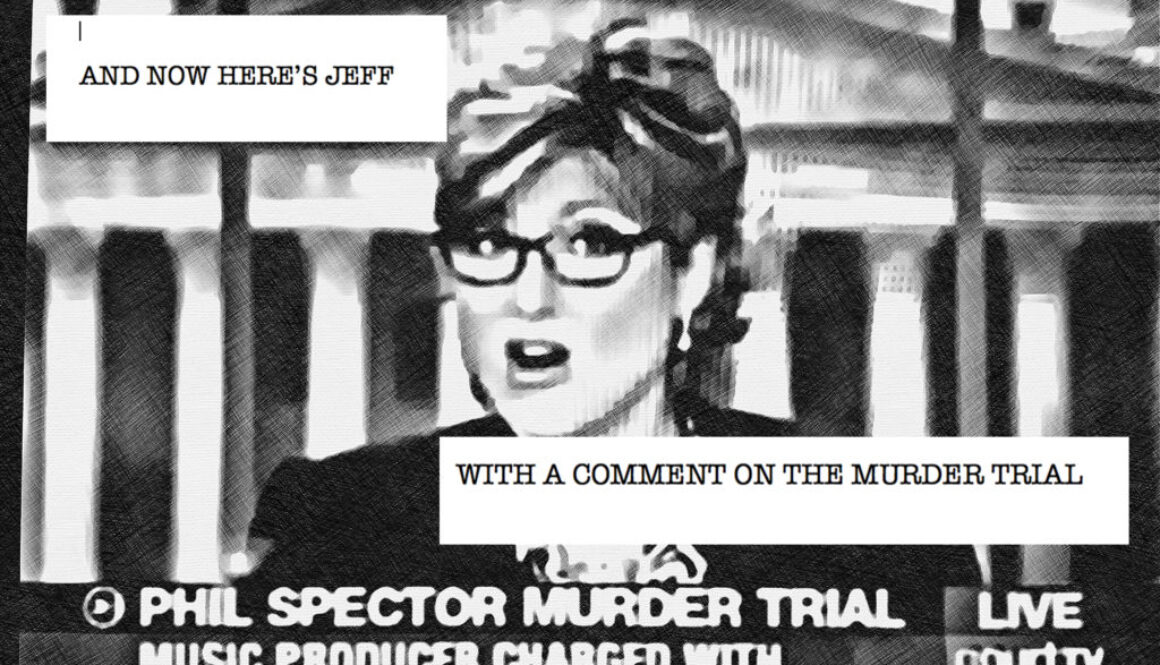

As a criminal defense lawyer who has tried several high profile criminal cases, I have often been asked why I refuse media requests to comment on the day’s current ‘sensational’ criminal trial. Even a cursory view of the media’s customary coverage of a ‘publicity case,’ makes it clear that my view is not shared by a number of my colleagues. Lawyers commenting on an on-going criminal trial seems to be an established part of the coverage format. Consequently, I thought a dissenting view might be of interest.

Our insatiable interest in any appalling or scandalous criminal trial is totally understandable. But satisfying this natural human curiosity is not the societal value we protect when we allow the news media to report on what happens in our courts. The press is given access in order to report whether anything improper or illegal occurs that would deny any citizen justice or due process. But this essential responsibility can be accomplished without reporting contemporaneously on the trial and digesting each day’s most ‘interesting’ testimony. In England the press is allowed to sit through every minute of a trial, but they are prohibited from reporting on it until the case is concluded. So there are other ways for a democratic country to protect the freedom of the press, short of our current approach.

What’s the Harm?

It was embedded in our Constitution that, in order to protect our individual freedoms, twelve random citizens from the community would decide the truth of any criminal charge brought by the authorities and not leave such decisions to government officials. Importantly, the jury’s decision is supposed to be based solely on the evidence the jurors hear in open court, not from any other source, so we can be assured that nothing was done secretly. Thus we do not allow outside people to speak to a juror about the case, or permit rumors to be discussed or witnesses not to be in open court and put under an oath to tell the truth.

Our courts have long recognized that the news coverage of a trial has the potential to violate the integrity of this process and effect its impartiality and transparency. It is in an effort to protect the jury from this outside influence that the judge at the beginning of such a trial orders the jurors not to listen to or view any news coverage. In fact, even the participating lawyers are often given a ‘gag order’ that prohibits them from talking to the press about the case.

Our courts have long recognized that the news coverage of a trial has the potential to violate the integrity of this process and effect its impartiality and transparency. It is in an effort to protect the jury from this outside influence that the judge at the beginning of such a trial orders the jurors not to listen to or view any news coverage. In fact, even the participating lawyers are often given a ‘gag order’ that prohibits them from talking to the press about the case.

However, unless jurors are sequestered in a hotel, it is impractical to expect to completely shield the jurors from such outside media influences, given how saturated our lives have become with electronic communications. Jurors who return home at the end of the court day end up watching TV with their families or see an alert on their cell phone that lets in the media’s outside views on the case.

The dangers to the integrity of the juror’s decision by such uninvited access and availability of the news media are serious and many faceted, so I’ll only consider a few. First, it is not uncommon for commentators to incorrectly report the testimony in court, which might confuse an exposed juror’s recollection. Second, the news coverage often speaks from one perspective about the perceived strength of the prosecution’s case, which can easily be interpreted as if they were speaking as the voice of public opinion. Hearing this, jurors may believe the public has a certain expectation of how the case should be decided and feel pressured to decide in accordance. They may even fear their colleagues’ disapproval when they return to work if they decide the case the “wrong” way. And some jurors may be persuaded by the opinion of an ‘expert’ legal commentator they hear about the credibility of a witness or the trial strategy. Or view negatively that the defendant does not testify after an ‘expert’ opines that given the state of the evidence the defendant must take the stand.

Even witnesses are not immune from the subtle influences of commentators and the resulting publicity. In publicity cases, some witnesses approach their courtroom testimony as a performance, upon which they anticipate they will be judged in the media. Such a witness will fortify a previous hazy recollection so as to appear confident or abandon their previous opinions out of fear of public censure. Others regard their appearance as their moment in the spotlight and embellish their testimony to garner more attention.

What are the “facts?”

It the juror’s responsibility to sort through the various contradictory versions of events presented to them and decide the “facts” of the case by deciding which testimony to believe. The news media, because of limited time or word space, only report the ‘facts’ that, in their opinion, are newsworthy. Legal commentators very rarely, if ever, sit through an entire trial or even an entire day of testimony. As a consequence, they base their opinions of TV segments or news reports. They may not even know the testimony of other witnesses on an issue or even the cross-examination of certain witnesses. And they certainly don’t know all the other facts contained in the reports in the files of the defense and prosecution. Such commentary is like writing a review of a book you have not read by relying upon the critique of another critic.

Even if the case has been completed, to comment on the lawyer’s trial tactics or strategy suffers from the same handicap. Without knowing all the facts and seeing how witnesses came across on the witness stand, another lawyer is not in a position to comment on tactical choices. As for the soundness of the verdict, that requires sitting through the entire trial, hearing all the witnesses and seeing the physical evidence. From a practical standpoint, it would be difficult to find a qualified trial lawyer who would abandon his or her practice to sit through an entire trail for the privilege of second guessing the jury or the lawyers.

As for me, I think our republic would survive if we adopted the British system and not have this piecemeal public examination intruding in our criminal trials. There is enough news to occupy us without meddling with our jury system.

Ed Rucker, one of the most prominent defense lawyers of our time, tried over 200 jury trials, representing defendants in 13 death penalty cases. His novel, The Inevitable Witness, an acclaimed legal thriller, includes the themes discussed in this article in a literary context, and is available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble or at a bookstore near you.