Toxic work cultures start with incivility and mediocre leadership. What can you do about it?

You’re in a meeting, with something important to say. Just as you begin, a colleague sighs and shares an eye-roll with their buddy. And not for the first time.

Workplaces aren’t always harmonious. Whether it’s a cafe, factory or parliament, people do and say hurtful things. They may talk down to you, “call you out” in front of others, make jokes at your expense, gossip about you behind your back, or give you the silent treatment.

This type of incivility doesn’t quite rise to the level where you can complain to human resources and expect a satisfying resolution. Organisations typically have policies against racism, sexism, harassment and other overt forms of abuse. But incivility – being less severe and more difficult to prove – tends to fly under the radar.

Most of us will experience incivility at some point at work. More than 50% experience it weekly. According to a 2022 meta-analysis of 105 incivility studies, you’re more likely to cop it if you’re new, female, in a subordinate position, or from an ethnic minority.

Unkind and thoughtless words matter. As linguist Louise Banks says in the 2016 film Arrival: “Language is the first weapon drawn in a conflict.”

What people say and how they say it affects us deeply. One cruel remark can ruin your whole day. Left unchecked, incivility makes for a toxic workplace.

Why are people rude to each other?

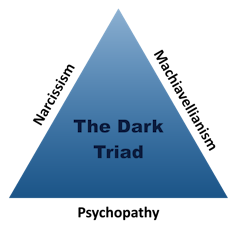

It’s tempting to simply blame bad character. Certainly such behaviour is much more likely from people with dysfunctional personality traits, especially the “dark triad” of narcissism, psychopathy and Machiavellianism.

Narcissists are self-obsessed and dominate social interactions. Psychopaths lack empathy and don’t understand social norms. Machiavellians are manipulative, self-interested and amoral.

But even “nice” people can be uncivil, with the three most common incivility triggers being because they feel let down by their leaders, are under more pressure than they can handle, or someone else was rude first – to them or others.

Incivility can therefore become a vicious spiral that turns victims and bystanders into perpetrators. That’s how toxic workplaces are born, develop, and perpetuate.

Incivility in the workplace

Leadership sets the tone. We’re social creatures and learn what’s expected and acceptable from those we look up to. Our leaders’ behaviour is infectious, and cascades down throughout and across organisations – for better or worse.

Incivility is most harmful when it comes from a supervisor: someone we’re supposed to trust, who’s supposed to look after us.

The power asymmetry means leaders’ inappropriate behaviour is less likely to be challenged. Take, for example, Harvey Weinstein, who for decades abused his position as one of Hollywood’s most successful film producers to sexually exploit women, before finally being held to account.

But managers can be derelict in their duty without being perpetrators. As in the case of sexual harassment, it may be easier to see and hear no evil, perhaps because the perpetrator is favoured as a high performer or a friend. With the capacity for one individual to make life a misery for many colleagues, this leadership failure can lead to a toxic workplace culture.

Authentic leadership ‘in the trenches’

It’s up to leaders to be the first movers against incivility and create positive work cultures with their own behaviour. What leaders will tolerate on their team sets the bar for how everyone else will behave.

With colleagues Stephen Teo and David Pick, I’ve surveyed 230 nurses across Australia about the leadership qualities that help reduce incivility.

Why ask nurses? Because their work is stressful and demanding. The strain of providing critical care for patients creates conditions conducive to conflict, from swearing to physical violence. Workplace incivility is frequent and these stressors increase the likelihood of medical mistakes. So there’s good reason to reduce incivility to improve health-care quality.

Our research shows that authentic leadership promotes workplace cultures with less incivility and better well-being. Such authentic leaders are aware of their own strengths and weaknesses, act on their values even under pressure, and work to understand how their leadership affects others.

What can you do?

Incivility isn’t okay. It should never be excused as “just part of the job”.

If this is happening to you, or others in your workplace, avoiding it won’t help you or your colleagues. Putting up with incivility is emotionally taxing, entrenches feelings of resentment and will likely lead to bigger conflicts down the track.

Responding with more incivility of your own isn’t a good idea. Retaliation rarely deters a person who engages in such behaviour and instead effectively endorses it.

One approach recommended by psychologists when dealing with high-conflict personalities is known as the BIFF technique: be brief, informative, friendly and firm.

When someone says something mean, you might respond, as calmly as possible, along the lines of: “Your comments are hurtful and damage our working relationship. Please, let’s keep things professional.”

If the behaviour persists, approach your supervisor. Again, stay calm. Explain what’s happening and how it’s affecting you. You don’t have to go at it alone either: consider inviting colleagues who can support you, and your claims.

Will this fix the problem? Possibly not. Your manager might simply shrug their shoulders, or arrange a “mediation” that resolves nothing. But saying and doing nothing will almost certainly leave you unsatisfied.

If your manager is the perpetrator, contact your HR department first (if your organisation has one) or else your union. The union can offer advice on other avenues to seek redress.

Statutory agencies such as Australia’s Fair Work Ombudsman, Employment New Zealand and the UK’s Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service have the power to investigate workplace complaints, and to intervene in disputes through formal conciliation or arbitration. But before embarking on such a process, it’s best to get expert advice. You might get justice, but also still need to find another job.

Incivility is unlikely to stop on its own, however. Your voice matters and can help break the cycle.

^^^

Lecturer of Leadership and Director of Academic Studies, Edith Cowan University.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation under a Creatives Commons License.

Feature image by Pavel Danilyuk.