A brief history of the Black church’s diversity, and its vital role in American political history

Jason Oliver Evans, University of Virginia

With religious affiliation on the decline, continuing racism and increasing income inequality, some scholars and activists are soul-searching about the Black church’s role in today’s United States.

For instance, on April 20, 2010, an African American Studies professor at Princeton, Eddie S. Glaude, sparked an online debate by provocatively declaring that, despite the existence of many African American churches, “the Black Church, as we’ve known it or imagined it, is dead.” As he argued, the image of the Black church as a center for Black life and as a beacon of social and moral transformation had disappeared.

Scholars of African American religion responded to Glaude by stating that the image of the Black church as the moral conscience of the United States has always been a complicated matter. As historian Anthea Butler argued, “The Black Church may be dead in its incarnation as agent of change, but as the imagined home of all things black and Christian, it is alive and well.”

As a scholar of Christian theology and African American religion, I’m aware of this long history of the Black church and its contribution to American politics. Its story began in the 15th and 16th centuries, when European empires authorized the capture, auction and enslavement of various peoples from across the coast of Western and Central Africa.

Origins of African American Christianity

As millions were transported through the “Middle Passage” to the Americas, Europeans forcefully baptized the enslaved into the Christian faith despite many of them adhering to traditional African religious systems and Islam. European slave traders dismissed Africans as “heathenish” to justify their enslavement of Africans and the coercive proselytization to Christianity.

In the 1600s, British missionaries traveled throughout the American Colonies to convert enslaved Africans and the Indigenous peoples of the continent. Originally, however, white slaveholders were hesitant to convert enslaved Africans to Christianity because they feared that Christian baptism would lead to the enslaved Africans’ freedom, causing both economic ruin and social upheaval. They widely supposed that British laws mandated the freedom of all baptized Christians, and thus white slaveholders initially refused to grant missionaries permission to instruct enslaved Africans into the Christian faith.

By 1706, six Colonies had passed laws that declared that Africans’ Christian status did not alter their social condition as slaves. Consequently, missionaries created “slave catechisms,” modified religious instruction manuals that instructed enslaved Africans about Christianity while reinforcing their enslavement.

Over time, evangelical Protestant groups followed suit in their proselytization of the enslaved community, most notably during the First and Second Great Awakenings, the Protestant religious revivals that swept across the American nation in the mid-18th and early 19th centuries.

Denominations that form the Black church

Both during and after the end of slavery, African Americans began to establish their own congregations, parishes, fellowships, associations and later denominations. Black Baptists founded first the National Baptist Convention USA, in 1895, the largest Black Protestant denomination in the United States. The National Baptist Convention of America International and the Progressive National Baptist Convention were founded years later.

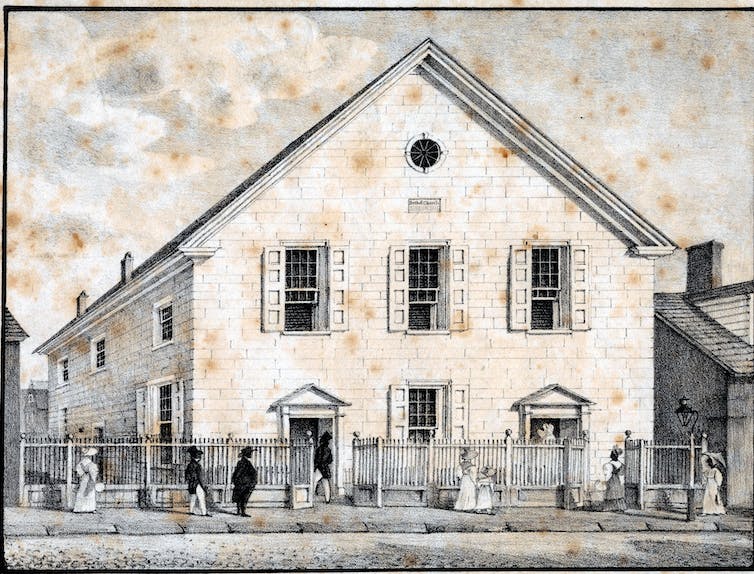

The first independent Black denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which was formalized in 1816, grew out of the Free African Society founded by Richard Allen, a former enslaved man and Methodist minister, in the city of Philadelphia in 1787. Allen and his colleague Absalom Jones walked out of St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church after white members demanded that Allen and Jones, who had been kneeling in prayer, leave the ground floor and go to the upper balcony, which was designated for Black worshippers.

Other Black Methodists founded two other denominations – the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in 1821 and the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church in 1870. The Church of God in Christ, the largest Black Pentecostal denomination in the United States, was founded by Charles Harrison Mason, a former Baptist minister, in 1897 and incorporated in 1907.

Other Black Christians belong to mainline Protestant denominations. Additionally, there are 3 million Black Roman Catholics in the United States, and a smaller number of African Americans who attend Eastern Orthodox churches. Moreover, a number of African Americans belong to independent nondenominational congregations, while others belong to white conservative evangelical, Pentecostal and charismatic churches.

Contributions to American politics

The Black church has played a vital role in the shaping of American political history. African American churches provided spaces for not only spiritual formation but also political activism.

Black churches were spaces where slave abolitionism was envisioned, and insurrections were planned. Black preachers such as Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner were actively involved in attempted and successful slave insurrections in the South

During the Reconstruction era, the African Methodist Episcopal Bishop Henry McNeal Turner served as one of the first African American legislators for the state of Georgia. Turner was famous for his scathing critiques of American Christianity and the nation at large. Ida B. Wells was an investigative journalist and educator who wrote extensive accounts of the lynchings of Black people in the South, fought against Jim Crow policies, and advocated for Black women’s right to vote. An active churchgoer, Wells also organized and led Bible study classes for young Black men at Grace Presbyterian Church, a predominantly Black church founded in 1888 in the city of Chicago.

Many Black Christians participated in the Civil Rights movement, including Bayard Rustin, an openly gay Quaker, who was instrumental in organizing the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on Aug. 28, 1963. Despite his contributions to advancing Black people’s freedom, Rustin was pushed to the background by his peers because of his homosexuality.

Pauli Murray, the first Black woman to be ordained in the Episcopal Church, was a lawyer, legal scholar, civil rights and gender equality advocate and poet. Murray compiled an extensive collection of laws and ordinances that mandated racial segregation and wrote extensively on women’s rights.

An influential institution

The Black church is far from monolithic. Its members hold different theological positions and hail from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, education levels and political affiliations.

Some African American Christians did not participate in efforts to end racial segregation, fearing violent backlash from white people. Today, Black Christians are divided over other social justice issues, such as whether to support LGBTQ equality. Nevertheless, African American Christians have drawn insights from their experience of enduring racism and their Christian faith to contest racial subjugation and advocate for their freedom and human dignity.

Despite the rise of the religiously unaffiliated or “Nones” within the African American community, the Black church, I believe, continues to be an influential institution.

^^^

Jason Oliver Evans, Ph.D. Candidate in Religious Studies, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: The exterior view of the Bethel African American Methodist Episcopal Church at 125 S. 6th St. in Philadelphia. Breton, William L., circa 1773-1855 Artist via the Library of Congress, World Digital Library